Strengthening Massachusetts’ Future:

Expanding the use of Fair Share Funds for Higher Education

February 2025

The Fair Share Amendment was designed to provide critical new investments in public education and transportation. While polls conducted by the MassINC Polling Group indicate public support for an equal split between transportation and education, the question of how the 50% allocated to education should be divided among early education, K-12, and higher education remains a topic of debate.

Several compelling factors suggest reassessing the current funding distribution patterns to ensure that these investments in public education fulfill the fairshare intent and address urgent need to enhance the quality of public education and the affordability of public colleges and universities.

The reasons are multifaceted.

Lack of Revenue Source Diversity

Compared to higher education, both early education and K-12 education benefit from diverse revenue source streams that provide greater financial stability and resilience. Massachusetts K-12 schools enjoy a diversified funding model—state contributions (40%), local revenue (52%), and federal aid—providing stability and resilience.

Early education and childcare have an even broader funding base—including federal and municipal governments, philanthropy, employers, and direct family contributions—making them inherently less dependent on state appropriations. While high-quality early childhood education is essential for child development, the primary function of childcare services is to support working families, making them more aligned with workforce policies rather than public education investments.

A recent analysis by the Rennie Center analysis shows that while the state’s investments continue to grow, employer contributions remain limited and lag behind. Encouraging better wages, employer-sponsored childcare benefits, and other private-sector strategies would prevent a disproportionate burden on public education funds and allow scarce public resources to be allocated more effectively. Ultimately, the state should adopt a strategic approach that recognizes childcare as both an economic necessity and a workforce support system, leveraging multiple contributors rather than relying too heavily on public education dollars.

In contrast, Massachusetts public higher education relies almost exclusively on state appropriations. Unlike 32 other states, Massachusetts offers no local funding for higher education, forcing institutions to offset insufficient state support by raising tuition and fees. Although higher education institutions benefit indirectly from federal funds through student financial aid, this reliance on students to cover shortfalls worsens the affordability crisis and underscores the urgent need for greater investment in higher education.

According to a study by EY-Parthenon presented to the Commission on Higher Education Quality and Affordability, the average student at public two and four-year institutions in Massachusetts faces $11,000 to $14,000 in annual out-of-pocket costs after all financial aid is considered. This level of "unmet economic need" compels a higher proportion of students to incur debt, with 63% of public university students taking on loans compared to 53% at private non-profit institutions. Consequently, the debt burden at graduation for students at public universities has begun to exceed that of their counterparts at private colleges.

Constitutional Intent and Mandate

The Fair Share Amendment earmarks revenues explicitly for "quality public education and affordable public colleges and universities," in addition to the maintenance of roads, bridges, and public transportation. This explicit reference to “public colleges and universities” as distinct from broader public education suggests a constitutionally recognized expectation to invest in higher education.

Traditionally, “public education” in this context has been understood to encompass K–12 and higher education, rather than early childhood programs or childcare services. While some early education initiatives, such as expanding universal Pre-K access in Gateway Cities, align with the goals of a high-quality public education system, the vast majority of Fair Share funds allocated to the Department of Early Education and Care (EEC) go toward childcare services. Over 90% of these funds support programs that, while essential for child development and workforce stability, extend beyond the conventional scope of public education.

Childcare services, unlike Pre-K expansion, primarily function as a social, economic, and workforce support—providing essential assistance to working families and strengthening labor market participation. While these services merit robust public investment, their alignment with the intended scope of the Fair Share surtax remains unclear. Allocating 15% of Fair Share revenues to these areas raises concerns about adherence to legislative intent and may divert resources from strengthening public K–12 schools and higher education.

Given the amendment’s language, there is a strong case for reviewing how these funds are allocated to ensure alignment with voter expectations and statutory requirements. Although higher education is explicitly included in the mandate, it is set to receive only 10% of Fair Share funds in the recently proposed supplemental and FY26 budgets—a figure that may not fully reflect the amendment’s priorities. To uphold the amendment’s intent, Fair Share funds should be directed toward core public education investments, including Pre-K where appropriate, rather than primarily funding childcare as a workforce service.

In light of these considerations, allocating at least 25% of Fair Share funds to higher education appears to better fulfill the amendment’s objectives. An allocation of up to 33% would also align with recommendations from the Board of Higher Education's recommendations. This approach not only adheres to legal guidelines but also reflects the electorate’s call to strengthen Massachusetts’ public education system.

Conclusion

Investing in higher education is not merely a budgetary decision—it is an economic imperative. Public higher education serves as a powerful engine of economic mobility, workforce development, and innovation, yielding returns that far exceed the initial investment. Every dollar allocated to higher education generates significant long-term economic benefits, increasing lifetime earnings for graduates, strengthening local industries, and expanding the state’s tax base. These returns not only justify but necessitate a higher and more stable share of Fair Share revenues for public higher education.

To fully realize the transformative potential of Fair Share revenues, Massachusetts must ensure a sustained and appropriate investment in higher education. A dedicated share of at least 25%—and up to 33%—is not just aligned with the constitutional intent of the amendment; it is essential for the state’s long-term economic vitality.

Learn More

Massachusetts’ Low Investment in Public Higher Education

Massachusetts allocates only 2.3% of its total budget to higher education, ranking among the lowest in the nation. This limited investment constrains resources available to students and institutions, intensifying financial pressures on both and threatening the long-term sustainability of the state’s public higher education system. This funding gap underscores the urgent need for the state to prioritize higher education and invest in more sustainable funding models to ensure quality, affordability, and accessibility for all students.

The Consequences of Chronic Underinvestment in Public Higher Education

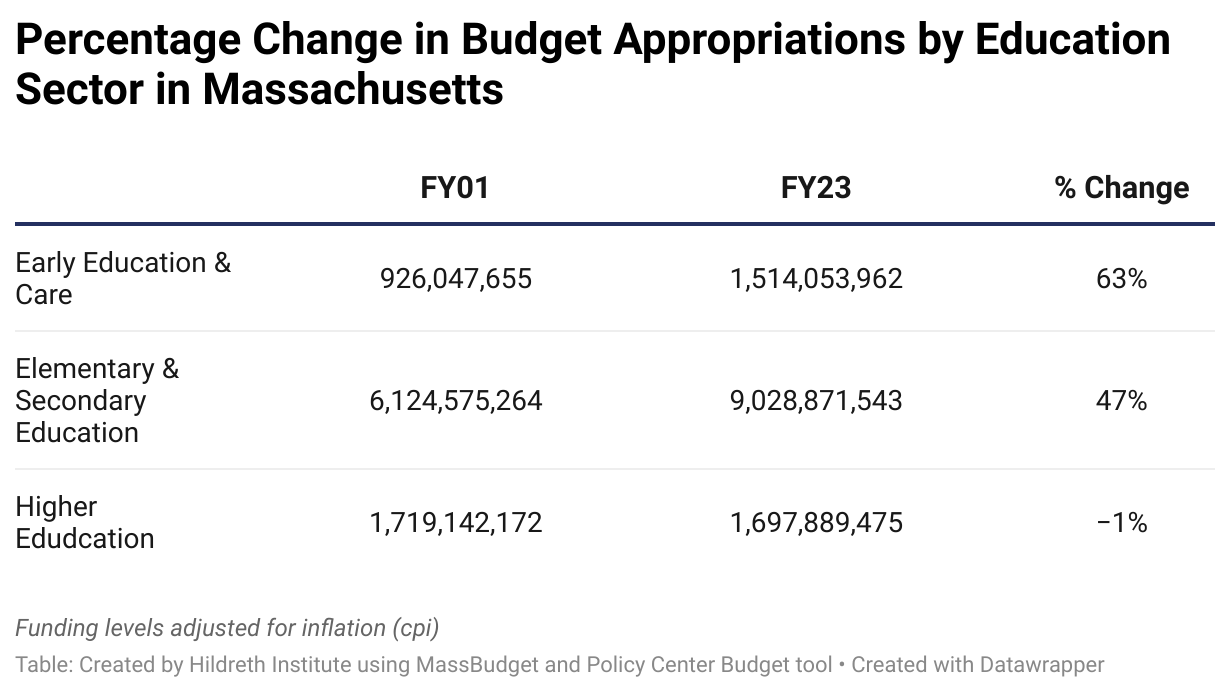

Massachusetts has long faced chronic underinvestment in its higher education system. Over the two decades before the introduction of Fairshare revenues, funding for early education and K-12 increased significantly, by 63% and 47% respectively. In contrast, funding for higher education not only stagnated but declined by 1%, after enduring cuts of over 10%. While the recent infusion of Fairshare revenues has begun to address this prolonged underinvestment, much more is needed to tackle the persistent affordability crisis and the broader challenges of student access and success, which continue to make public colleges and universities increasingly out of reach.